The boy-love bookshelf - Remembering Chester Arthur

By: Robert Rockwood

John Valentine, Puppies (London: Gay Men's Press, 1988), 174 pages, $9.50.

This review of Puppies is intended as an elegy for its author, who died in April of liver cancer. A lover of teenage boys, and one of the best friends I ever had, this man courted me for five years, starting when I was 15. C.V.J. Anderson, whose full name was Chester Valentine John Anderson, wrote the boy-love underground classic Puppies under the name John Valentine. Originally published in 1979, Puppies is a series of journal entries depicting man/boy sexual encounters, mostly one-night stands in Los Angeles in the early 1970s. It is also a lyrical celebration of the author's real-life veneration of teenage boyhood:

I undress him very slowly, like unwrapping a present, enjoying every particle of the process. The muflled map of buttons loosed, the sliding of the shirt up that smooth way &, savoring, over the head & off of the quasi-dormant arms... The usual complications at the belt buckle, vain struggle to open it, a hassle - then his hands charmingly sneaking in to solve the buckle with one practiced motion & then sneaking off again to play dormant...

Freeing the hips from the tubular Levis. He humps his ass dormantly to ease them down. It's like a pile of dirty clothes giving birth to a puppy. Down the columns of his legs - smooth to touch & the hair soft. Taking care the pants don't bunch up & get awkward to remove. Past the knees, nearing ankles. He hadn't counted on nakedness, but you can feel his mind change in the texture of his calves. Then over the ankles & up off the feet & tossed cavalierly behind me to the

floor. Peel off the stockings as well...

Flow back up the tree of his body, taking it by inches & claiming it. To the swell of thighs & in to cock. Handle same, deal lovingly therewith, promising, and flow on, hand devouring contours, the delicate geometry of boy in his fullness:... the sphere of shoulder, throat & nape, that jaw, those ears, this forehead, hair. He hadn't expected to be kissed, either. Certainly he hadn't expected to kiss back...

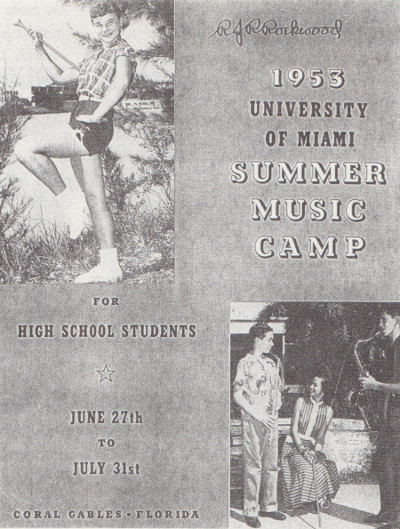

I met Chester Anderson in 1953 at a high school summer music camp at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida. I had just turned 15, and Chester was almost 21. A music student, majoring in composition, Chester held a flute scholarship in the University of Miami Symphony Orchestra, which at that time was a student/professional organization, performing a regular concert series at Miami Beach. Chester approached me one Saturday as I was putting away my flute after rehearsal. He was holding a copy of that year's music camp brochure, featuring a cover photo in which I stood holding my flute while cracking jokes with a majorette and a saxophone player. Introducing himself in a droll, charming way, Chester said he'd been admiring my picture and had wanted to meet me. He explained that he was a U of M student and also a flute player. He said he worked in the U of M music library, had access to some fascinating flute music, and wondered if I would like to play duets with him.

Music campers had Saturday afternoons free, so instead of getting on the bus and going into Miami, Miami Beach, or Coral Gables, I followed Chester to his apartment. I was perfectly aware that this fascinating stranger was interested in making more than music, so after we finished one duet I would tease him by turning the page and saying "That was just great! Let's do another." After several hours of this, Chester pointed to his bed and said "If playing duets makes you as horny as it does me, why don't we do something about it?" Still teasing, I said "Music sounds the way sex feels. I don't generally waste time with sex if I can make music instead."

After that, Chester and I played duets every Saturday afternoon during the remaining weeks of music camp. As soon as camp was over, we continued our relationship by gleefully conspiring to engage the US Postal Service in what seemed at the time the ultimate safe sex - screwing each other with words hermetically sealed in an envelope and sent through the mail.

The summer of 1955 I was back at high school music camp, this time as a counselor, responsible for twenty 12- and 13-year-old boys. Counselors had Thursday evenings off, in addition to Saturday afternoons, so Chester and I made music twice a week. Chester's appearances at the dormitory to pick me up would result in wildly scurrying feet, excited treble voices shouting "Chester's here," and little boys milling around, tugging at Chester's sleeve - flirting, bantering, telling jokes as though the man were some sort of queen bee. I doubt that the boys consciously understood what kind of music Chester and I were engaged in, but they instinctively recognized that Chester was the witty co-conspirator, wise sexual ally, and naughty uncle that young boys often fantasize about.

The summer of 1957, after graduating from high school, I played in the orchestra of a summer music festival in another state. This was arranged by Chester, who was a friend of the music director, a brilliant conductor who was also a boy-lover. Chester was at the music festival only for the final two weeks, but our previous exchange of letters had already become an open form of erotic public entertainment.

Because I wanted to be near Chester, I attended the University of Miami, instead of an Eastern Ivy League university that might have been the more appropriate choice. At that time Chester worked in Miami Beach as assistant manager of the Travellers Motel (he mentions this motel by name in Puppies), but during my sophomore year he moved to New York, and a McDougal Street address. The last time I saw him in Miami, in 1961, he had taken up the alto recorder. Always a superb flutist, his recorder playing was virtuosic. I've never heard anyone play Telemann's recorder sonatas more beautifully than he did.

As readers of the NAMBLA Bulletin may surmise, "The Boy-Love Bookshelf" columns reflect a point of view that Chester must be given credit for helping pound into shape, for his influence penetrated to all aspects of my mental life. Space does not permit more than one example, but this is the most significant of all. In the June, 1991 issue of the NAMBLA Bulletin I analyzed Richie McMullen's Enchanted Boy (London: Gay Men's Press, 1989) and Enchanted Youth (London: Gay Men’s Press, 1990) in terms of esoteric alchemy. Chester would have appreciated that piece, since it owes much of its audacity to him. After reading the compendium of Jewish hermetic mysticism known as Cabala, Chester read everything hermetic that he could lay his hands on, including an early edition of C.G. Jung's Psychology and Alchemy. Thus it was Chester who first introduced me to Jung and to Jung's discovery that alchemy was neither chemistry nor metallurgy but psychology.

As a college sophomore I mentioned to Chester that I was reading excerpts from Spenser's Faerie Queene in one of my literature classes. I was surprised to discover that Chester seemed to know the poem. Playing the guru, Chester said "Spenser states that the Faerie Queene is a 'magic' poem. No one knows what the poem really means, because no one takes Spenser at his word. But someday someone will." I remember blurring out, half facetiously, "Chester, you're looking at that someone." Years later, the seeds that fairy godfather Chester planted in me engendered my Ph.D. dissertation, Alchemical Forms of Thought in Book I of Spencer's "Faerie Queene" (University of Florida, 1972), in which I took Spenser "at his word" and demonstrated that Spenserian "magic" is the psychology of spiritual transformation.

In Puppies Chester Anderson carved his own epitaph: "Teenage boys, gentlemen! There's the drug that's ruined me. It's that lust made me what I am. That's the appetite that spoiled my chances for a successful, happy life in the real world of the majority."

Chester's self-judgment implicitly accepts society's condemnation of man/boy love, and is, so to speak, tongue-in-cheek. After all, it was Chester who finally convinced me that it is wrong to feel guilty about love. As one of the teenage boys who contributed to Chester's supposed "ruin," I can personally attest to the positive effect he had on the lives of those he touched. Some of my fondest memories are associated with C.V.J. Anderson alias John Valentine, whose friendship provided the waning years of my boyhood with much of its sweetness, and most of its magic.

source: Article 'The Boy-Love Bookshelf - Remembering Chester Arthur' by Robert Rockwood; NAMBLA Bulletin; September 1991